I am spending this week in Budapest in order to participate in the 6th European Set Theory Conference, and I want to take the occasion to present a nice little result of Paul Erdős, one of the great mathematicians of the twentieth century, who was born and spent the first decades of his life in Budapest before spending most of his adult life traveling the world, living and working with a vast network of mathematical collaborators.

Erdős contributed to a huge array of mathematical disciplines, including set theory, my own primary field of specialization and the field from which today’s result is drawn. Like most other Hungarians working in set theory, Erdős’s results in the field have a distinctly combinatorial flavor.

In order to state and prove the result, we need to review a bit of terminology. Recall first that the Continuum Hypothesis is the assertion that the size of the set of all real numbers is , i.e., that there are no sizes of infinity strictly between the sizes of the set of natural numbers and the set of real numbers. As we have discussed, the Continuum Hypothesis is independent of the axioms of set theory.

The Continuum Hypothesis can be shown to be equivalent to a surprisingly diverse collection of other mathematical statements. We will be concerned with one of these statements today, coming from the field of graph theory. If you need a brief review of terminology regarding graphs, visit this previous post.

If is a set, then we say that the complete graph on

is the graph whose vertex set is

and which contains all possible edges between distinct elements of

.

If is a graph and

is a natural number, then a

-cycle in

is a sequence of

distinct elements of

,

, such that

are all in

.

A graph without any cycles is called a tree. (Note that many sources require a tree to be connected as well as cycle-free and call a cycle-free graph a forest. This leads to the pleasing definition, “A tree is a connected forest.” We will ignore this distinction here, though.)

A complete graph is very far from being a tree: every possible cycle is there. We will be interested in the question: `How many trees does it take to make a complete graph?’

Let us be more precise. An edge-decomposition of a graph is a disjoint partition of

, i.e., a collection of sets

, indexed by a set

, such that

for distinct elements

and

. An edge-decomposition thus decomposes the graph

into graphs

for

.

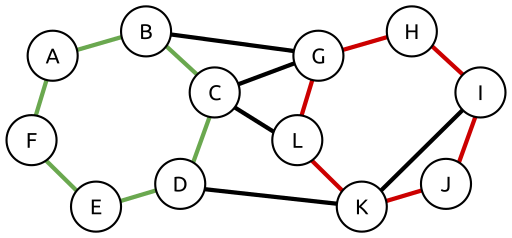

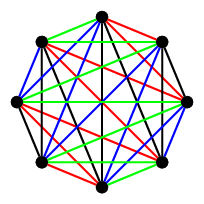

We will be interested in the number of pieces required for an edge-decomposition of a complete graph into trees. In the above image, we provide an edge-decomposition of the complete graph on 8 vertices into 4 trees (in fact, into 4 Hamiltonian paths). For an infinite complete graph, though, no finite number of pieces will ever suffice. The question we will be interested in today is the number of pieces necessary to provide an edge-decomposition of the complete graph on the real numbers, , into trees.

Theorem. (Erdős-Kakutani and Erdős-Hajnal) The following statements are equivalent:

- The Continuum Hypothesis

- There is an edge-decomposition of the complete graph on

into countably many trees.

Proof. Suppose first that the Continuum Hypothesis holds. Then can be enumerated as

. For all

, we know that

is countable, so we can fix a function

that is one-to-one, i.e., if

and

are distinct ordinals less than

, then

.

We now specify an edge-decomposition of the complete graph on into countably many graphs. The edge-sets of these graphs will be denoted by

for

. To specify this decomposition, it suffices to specify, for each pair

of countable ordinals, a natural number

such that

. And we have a natural way of doing this: simply let

.

We claim that each is cycle-free. To prove this, suppose for sake of contradiction that

and

has a

-cycle. This means there are distinct ordinals

such that

are all in

.

Now fix such that

is the maximum of the set

. Without loss of generality, let us suppose that

(if this is not the case, simply shift the numbering of the cycle). Then we have

. Since

, our definition of

implies that

, contradicting the assumption that

is one-to-one and finishing the proof of the implication

To prove that implies

, we will actually prove that the negation of

implies the negation of

. So, suppose that the Continuum Hypothesis fails, i.e.,

. Let

be an enumeration of

, and suppose

is an edge-decomposition of the complete graph on

. This means that, for all pairs of ordinals

smaller than

, there is a unique natural number

such that

. We will prove that there is a natural number

such that

contains a 4-cycle.

Let be the set of ordinals that are bigger than

but less than

. Clearly,

. For each

and each

, let

be the set of ordinals

less than

such that

. Then

, so, since

is countable and

is uncountable, there must be some natural number

such that

is uncountable. Let

be such an

.

For , let

. Then

. Since

, this means that there must be some natural number

such that

.

Now, for each , let

and

be the least two elements of

. Since there are only

different choices for

and

, and since

, it follows that we can find

in

and

such that

and

. It follows that

. In other words,

forms a 4-cycle in

. This completes the proof of the Theorem.

Notes: The proofs given here do not exactly match those given by Erdős and collaborators; rather, they are simplifications made possible by the increased sophistication in dealing with ordinals and cardinals that has been developed by set theorists over the previous decades. The implication from 1. to 2. is due to Erdős and Kakutani and can be found in this paper from 1943. The implication from 2. to 1. was stated as an unsolved problem in the Erdős-Kakutani paper. It was proven (in a much more general context) in a landmark paper by Erdős and Hajnal from 1966.